Torque Controller for Robot Manipulators

November 25, 2024

This post explains the importance of torque-based controllers that send torque/force commands for robotic arms and illustrates the difficulty of using them for any robotic arm through ROS 2 and Gazebo Sim. It starts by demonstrating the challenges of using the existing C++ plugins for ros2 controllers. Then, with the aid of classical control theory, this post illustrates how to bridge the gap. Consequently, the robotic arm doesn't collapse to the ground. It holds its position through torque commands generated internally and switches to an external input supply when another node sends the torque command.

1. Introduction

Many robot applications tackle external disturbances whose presence makes robots challenging to control with just position or velocity commands or simply kinematic control [1]. For example, drones navigate through wind gusts, and robot manipulators handle varying payloads, or mobile robots navigate in rough terrains [#1]. In all such scenarios, these agents are subjected to non-parametric exogenous disturbances (since the disturbances cannot be modelled as a function of the system's state) and parametric disturbances (such as damping friction). Moreover, kinematic control strategies fail to reject these disturbances, failing the robot to achieve prescribed tasks (like trajectory tracking or point-to-point motion). To tackle this problem, researchers leverage the dynamics of the given system (robotic arm drone or mobile robot) so that controlled inputs to the system can avoid the issues mentioned earlier. In other words, if we supply enough control input based on the system's dynamics to handle exogenous disturbances, the prescribed task can be availed without failures. In addition, most systems, like robot manipulators, are comprised of actuators that take dynamical inputs, i.e., torque, that can handle the problems mentioned above.

This discussion motivates us to implement the torque-based controller on a robot system. However, a wise engineer recommends testing your simulation first. If your tests are positive, go for hardware implementation. In addition, many challenges occur during implementation when sending the control inputs directly to the robot. Some of them are mentioned below.

- Deterministic implementation

- Meeting the real-time expectation

- What should happen to the robot when no control inputs are given? Do we expect it to stay at the last position or something else amid operation?

In another post, I will address points (1) and (2) in detail. The main focus of this article is regarding point (3). In practice, if you do not send the torque commands to the robot, it essentially implies that zero control input is given at the instant. This situation can be catastrophic, leading to the destruction of equipment or, worse, amid the operation. I consider the robotic manipulators for demonstrating these effects in the rest of the discussion. Also, illustrating these effects on real robots is dangerous and not economic in nature. Therefore, I shall demonstrate it through the simulations in the gazebo. Moreover, this post also concerns the existing ros2_controllers and its limitations in direct implementation in simulation.

2. Problems

To replicate the problems or solution from here onwards, I shall narrate the sequnce of steps to complete this quest. In addition I am considering KUKA LBR IIWA 14 R820 industrial robot manipulator for simulations. Firstly, I recommend installing the following repo on torque controllers.

- Requirements: Ubuntu 24.04, ROS 2: Jazzy Jalisco,

ROS 2 controllers,

Gazebo Harmonic,

gz-ros2-control sudo apt install ros-$ROS_DISTRO-pinocchio- Clone the repository into the workspace

git clone https://github.com/Shravista/torque_controllers.git - Compile the package with

colcon build --symlink-install. Then, launch the bringup file

ros2 launch example_robots iiwa14_bringup_launch.py 'controller_name:=iiwa14_effort_controller'Then, observe that the robot falls down immediately after the bring-up file is launched.

Let us try to use the "Mouse Drag Tool" (see the Animation below for instructions on how to enable it) to try lifting the robot by using Ctrl + right-click on the mouse and then start lifting the robot. You will observe here that the robot falls down again, right? Well, this action is because no control input is provided, and gravitational forces are doing their duty.

Suppose we have an external agent that can supply appropriate torque commands to the robot to overcome the gravity forces and reach the target position. This is precisely what we can do by running the following program ( I will shed more light on what this program does in the background a bit later).

ros2 run torque_control_tests iDControl --ros-args --params-file <Path to src folder of Workspace>/torque_controllers/torque_control_tests/config/inverseDynamicsControl.yamlNow you observe that the robot reaches the target joint angular position with $q_{\text{desired}} = [0,0,0,0,0,0,0]^\top$ and stays there. Then repeat the same experiment with the "Mouse Drag Tool" to disturb the robot and observe two things: 1. it is a bit harder to drag the robot, and 2. if you stop disturbing the robot, it eventually reaches and stays at $q_{\text{desired}}$.

By the way, you can change the $q_\text{desired}$ in the following manner.

ros2 run torque_control_tests iDControl < enter the seven joint angle positions in degrees each separated by a space > --ros-args --params-file /home/shravista/muse_ws/src/torque_controllers/torque_control_tests/config/inverseDynamicsControl.yamlAt least, we can say that this is a bit satisfactory for making the robot stand. So, stop the program (ctrl + C). We see here again that the robot falls. It is the limitation of ros_controllers implementing the naive effort_controllers without realizing its effect when no control input is provided.

In Summary, we want to have gravity compensation, i.e., the robot should withstand the gravity forces when no control input is provided. So, the functionalities of the new controller must have the following:

Goals:

- Hold the robot position by sending the nominal torque input to counter gravity or any external forces.

- Switch these nominal inputs to external torques supplies when another agent feeds the control inputs. (I assume the agent sends the appropriate control torque inputs to stabilize the system).

3. Solution

One can infer that The easy-go solution is a switching controller strategy between the nominal torque inputs and control input sent by the external agent. So, How do we do this? We implement the same control policy as in the previous illustration but at the root of the ros2 controller interface. It solves the problem of robot inability of holding its position as soon as the simulation is brought up. It switches the control input when another agent sends it by subscribing to the other agent's commands.

3.1 Behind the scenes so far

Firstly, the program we ran earlier implements the inverse dynamics control, which can be synthesized through feedback linearization [1]. This strategy is also called control-law partitioning [2]. By the way, what is inverse dynamics (highlight box)?

Forward Dynamics:

It is to determine the generalized acceleration, velocity and position (joint accelaration, velocity, & position for manipulators) resulting from the applied external force or moment (joint torque).

Inverse Dynamics:

It is to determine the net external forces (joint torque) to generate the motion specified by accelarations, velocities and positions.

To begin with, robotic manipulator dynamics are described by the Euler-Lagrangian modelling that consists of $\boldsymbol{M}(\boldsymbol{q}) \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}$ is mass matrix, $\boldsymbol{C}(\boldsymbol{q}, \dot{\boldsymbol{q}}) \in \mathbb{R}^{n \times n}$ is Coriolis and centripetal matrix, $\boldsymbol{G}(\boldsymbol{q}) \in \mathbb{R}^n$ is gravity tprques induced by gravity vector , (currently, I have ignored friction forces and external disturbances for ease of understanding) and see how can use this description of dynamics to control the robot as we desired.

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{M}(\boldsymbol{q})\ddot{\boldsymbol{q}} + \boldsymbol{C}(\boldsymbol{q},\dot{\boldsymbol{q}}) + \boldsymbol{G}(\boldsymbol{q}) = \boldsymbol{u} \label{eq:EOM} \end{equation}Since we know that gravity forces are one of the main factors to pull down the robot, can we take u = g(q) to counteract the gravity forces? Well! lets test this hypothesis by directly implementing it in simulation. Run the following program.

ros2 run torque_control_tests gravityCompensation --ros-args --params-file <PathToWorkspace>/torque_controllers/torque_control_tests/config/inverseDynamicsControl.yamlWhat did you observe?

You see here that the robot tries to reach goal very slowly to origin and the control input $\boldsymbol{u}=\boldsymbol{G}(\boldsymbol{q})$ cannot oppose those of internal or external forces. It is because we have just pushed against the gravity forces, but what about the inertial forces or the Coriolis forces induced during motion or reaching the target? Therefore, one's task is to synthesize the control input ($\boldsymbol{u}$) to handle the external disturbances and take the robot from the current location to the target.

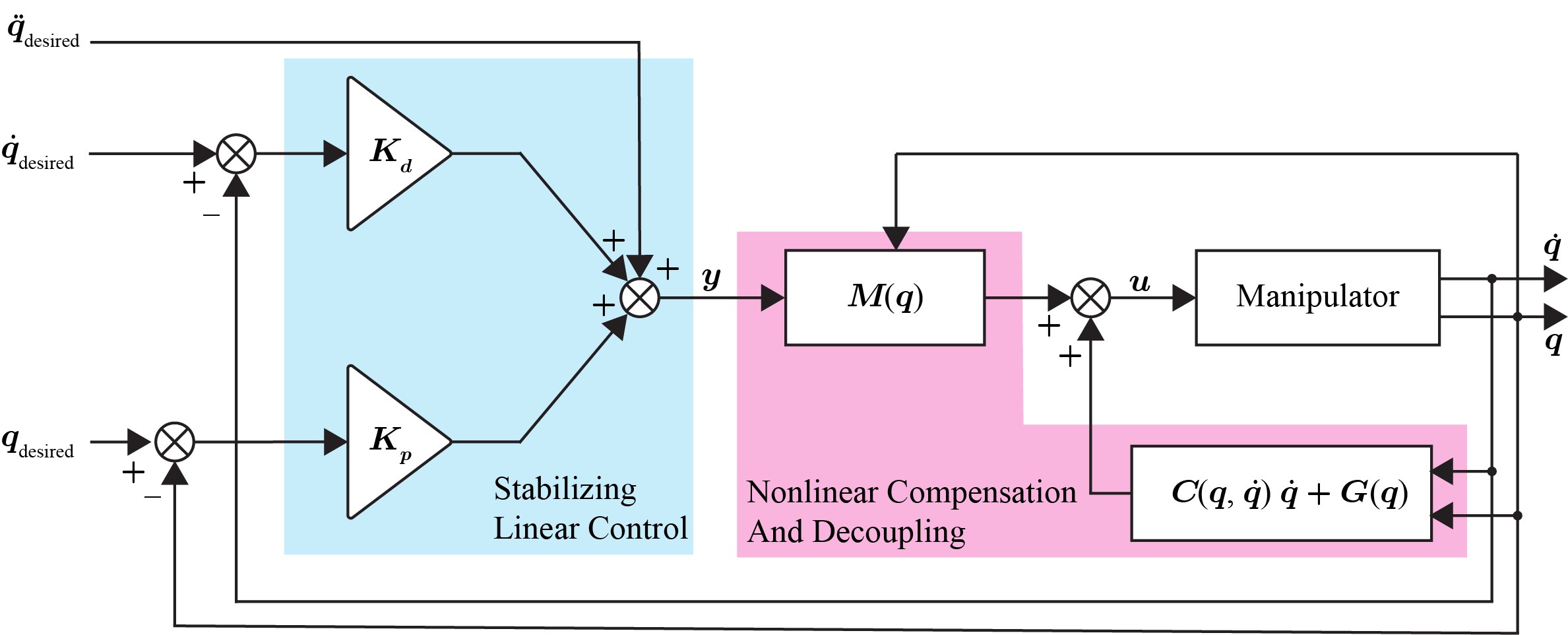

In this regard, our earlier program we have ran, utilizes the inverse dynamics controller $\eqref{eq:IDC}$ and Figure 1 developed for this objective (see the Fig. for more details). Let $\overline{\boldsymbol{q}} = \boldsymbol{q}-\boldsymbol{q}_\text{desired}$,

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{u} = \boldsymbol{M}(\boldsymbol{q})\left (\ddot{\boldsymbol{q}}_\text{desired} -\boldsymbol{K}_p\overline{\boldsymbol{q}} - \boldsymbol{K}_d\dot{\overline{\boldsymbol{q}}}\right ) + \boldsymbol{C}(\boldsymbol{q},\dot{\boldsymbol{q}}) + \boldsymbol{G}(\boldsymbol{q}), \label{eq:IDC} \end{equation}

where $\boldsymbol{K}_p,\ \boldsymbol{K}_d \in \mathbb{R}^{n\times n}$ are user-defined positive definite diagonal matrices. Further, larger the gains implies faster the convergence which becomes more evident in $\eqref{eq:asymp}$. Notice that if you had to substitute this controller $\eqref{eq:IDC}$ into $\eqref{eq:EOM}$ and by inherent properties of mass matrix, $\boldsymbol{M}(\boldsymbol{q})$ which is a symmetric and positive definite matrix, from $\eqref{eq:asymp}$ we can see that the current state exponentially converge to the desired value, i.e. ${\boldsymbol{q}}\to\boldsymbol{q}_\text{desired}$ as $t\to\infty$.

\begin{flalign} \ddot{\overline{\boldsymbol{q}}} + \boldsymbol{K}_d\dot{\overline{\boldsymbol{q}}} + \boldsymbol{K}_p\overline{\boldsymbol{q}} &= \boldsymbol{0}_n \notag \\ \implies \overline{\boldsymbol{q}} &= e^{-\boldsymbol{K}_pt}\boldsymbol{c}_1 + e^{-\boldsymbol{K}_dt}{\boldsymbol{c}}_2 \label{eq:asymp} \end{flalign} where $\boldsymbol{c}_1, \boldsymbol{c}_2 \in \mathbb{R}^n$ are some constants that take some form resulting in solving the above ODE. Moreover, the analysis provides one more insight that this controller always works with the assumptions No constraints on the system are imposed and controller can handle some level of bounded disturbances.3.2 Solution for goals

But how can we even implement this strategy for goals 1 and 2, as this strategy is meant for tracking both position and velocity? Instead, our goal 1 is supposed to bring down the velocity to zero, and we don't care what position the robot is currently in as long as the current configuration is in its workspace. Looking at the controller policy in $\eqref{eq:IDC}$, we can do either of the following:

- Make $\boldsymbol{K}_p = \boldsymbol{0}_{n\times n}$

- substitute $\boldsymbol{q}_\text{desired}(t) = \boldsymbol{q}(t),\ \forall t$ i.e. position target is always the current position.

Either of these two case results similar to $\eqref{eq:asymp}$, i.e. $\dot{\overline{\boldsymbol{q}}} = e^{-\boldsymbol{K}_dt}\dot{\boldsymbol{q}}(0)\implies \overline{\boldsymbol{q}} = \overline{\boldsymbol{q}}(0) - \boldsymbol{K}_d^{-1}e^{-\boldsymbol{K}_dt}\dot{\overline{\boldsymbol{q}}}(0) $.

In simple language we are giving more weight for the controller to suppress the joint velocity to be zero all the time and don't care about what the joint angular position should be.

Warning: Since velocity goes to zero as time goes to infinity, one can observe the drift in position very slowly. However, the convergence rate on the velocity state can be altered through gains ($\boldsymbol{K}_d$).

Now, let us come back to our simulation to understand this strategy.

- Lets rerun the simulation setup and run the following program.

ros2 launch example_robots iiwa14_bringup_launch.py 'controller_name:=iiwa14_effort_controller'ros2 run torque_control_tests iDControl --ros-args --params-file <Path to src folder of Workspace>/torque_controllers/torque_control_tests/config/inverseDynamicsControl.yaml

ros2 run rqt_reconfigure rqt_reconfigureIt's cool, right? With this, we have achieved the first goal. But, if we stop the p{rogram again, we still face the robot's problem of losing its position rapidly. In addition, we still need to switch between the IDC controller with $\boldsymbol{K}_p = \text{diag}\{0,0,0,0,0,0,0\}$ and the new controller to satisfy the given goal. However, writing the same in every program and attaining our goals (1) & (2) is cumbersome. In this regard, one can utilize the C++ plugins that we are using indirectly through ros2 controllers (effort_controllers/JointGroupEffortControllers).

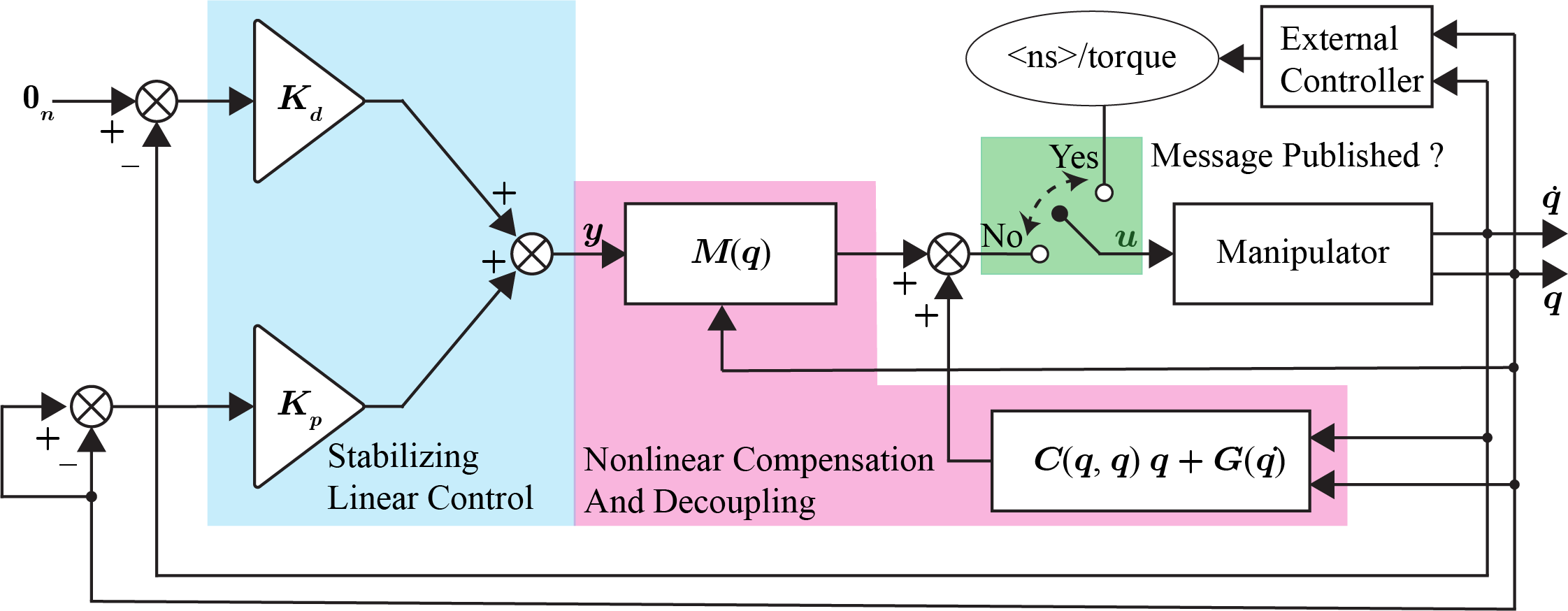

Since the existing implementation has limitations, as we discussed so far, I have developed the controller plugin [4, 5] in ROS 2 that can effectively handle both goals (See the Figure 2 We will use the same launch file as previous one but with the newly updated controller plugins as shown below:

ros2 launch example_robots iiwa14_bringup_launch.py 'controller_name:=iiwa14_torque_controller'Observe that in comparison to the previous plugin, the robot doesn't collapse and indeed stays in its initial position that was set in the URDF file. To demonstrate the goal (2), run the following program. This program is the same as before, but the only difference is that a reference trajectory is given instead of a position target. Finally, stop the program and observe that the robot has stayed on track because the controller plugin is loaded in the background; it ensures the robot keeps receiving the torque commands that hold its last known position when no external inputs are received.

Lastly, I encourage readers to explore more about the torque controllers and let me know any issues when using this repo. Kindly raise the issues in the github and I will clear them as soon as possible.

Limitations

- The nominal torques generated by inverse dynamics comtroller assumes the model parameters.

- Though it can be shown that these generated control inputs guarranteed to converge in presence of damping friction, but it may or may not work in presence of exogenous disturbances.

- Real time capabilities or deterministic of controller is still in questionable stage as I haven't been able to test it on real system.

Note that the first two points can easily be addressed and there exists several controllers that can do this job for you. Key idea here is those controllers should be decoupled to suppress the tracking in position and only velocity should be controlled. The last point, i will most likely to address this in next couple of months.

References

- B. Siciliano, L. Sciavicco, L. Villani, and G. Oriolo, Robotics: Modelling, Planning and Control. Springer Publishing Company, Incorpo- rated, 2010.

- Craig, J.J., 2006. Introduction to robotics. Pearson Educacion.

- S. Macenski, T. Foote, B. Gerkey, C. Lalancette, and W. Woodall, ‘Robot Operating System 2: Design, architecture, and uses in the wild’, Science Robotics, vol. 7, no. 66, p. eabm6074, 2022.

- ROS 2 controls: https://control.ros.org/

- Shravista Kashyap. Torque Controller [Computer software]. https://github.com/Shravista/torque_controllers.git